When walking home alone at night isn’t as simple as “Be Safe”

Animation by Holly Summerson

Sound Design by Adam McCallum

When walking home alone at night isn’t as simple as “Be Safe”

Animation by Holly Summerson

Sound Design by Adam McCallum

The sun burns the back of my neck, but the sky looms sea blue and I take the hint. Grains of sand increasingly cake the cracks in my feet, and I hanker after the water.

It’s been a long day and it’s only noon. We set out early, and slowly marched North. The Highland mists sank murky to greet us, before clearing a path as we crossed the bridge to the Isle. Inwardly eager to get digging, outwardly tired, faces slumped against the minibus windows. Our view of vast lushness, the reward for all the rain, plays pretend. I’m promised tropical seas, that if I “didn’t know any better would have me convinced I were at the equator”. Or so I’ve been told.

Left, right, left, right, one after the other, steady and rhythmical, and ready for a rest. A cool saltiness crackles in the air, and the crest of the sand bank beckons.

When I read about the island as a child, I asked, much to my parents’ amusement, “What are the Brothers pointing to?” “No”, replied Mum, patiently, “the point belongs to the brother.” Leaving me to wonder what point the brother made or owned, at Rubha nam Brathairean.

The pool of water soaks and covers my toes, reaching a few inches deep. It doesn’t carry the coolness all around me quite yet, but it will.

It starts to rain, as soon as we dock. I fetch my mac out of my backpack. It sticks to my skin all plastic and yellow. The tide may turn yet though, the breeze is brisk, and shaded clouds move fast above me, as if they’re late for something too.

The tide has turned, it’s coming in, those few inches now chase my knees.

It’s not quite the quicksand of childhood scares, but still it’s unexpected when my booted foot sinks. The tide is only just receding, and the land it leaves behind is sopping. There’s a leak in my boot, too. The sea, rinsing and washing clean each day’s detritus, has its own secrets. Jagged rocks on the tidal platform shine black and glint, tricking my eye. Over there, by the edge, there’s what looks like a wide circle, with smaller dots around and ahead of it. Like carefully laid out settings for stones. Or, toes. And it’s not alone.

The hills puff up kettle steam,

the loch is one big mug of tea.

My train rattles round

making noises like

a spoon tapping

along the banks,

clink clink.

The denser weather

closing in,

someone’s pulling the drawstrings.

Tissue paper torn and laid together,

waves where the sticky tape

doesn’t hold;

A flimsy fan in the face of a mere breeze .

Pressure funnels

air up

we head into a tunnel of mountain cloud,

darker now,

resembling a smoker’s exhaled breath

on a cold day.

EMC

Loch Lomond, Gustave Doré

Now the weather is getting bright it’s time for more walks and wanders. If you find yourself at a loose end in the city why not take a tour and stop by some of these hidden sculptural gems.

The Hunterian, soon to turn 300 years old, has its very own sculpture garden adjacent to the Art Gallery off University Avenue. This little haven is a sun trap in the summer and is mostly discovered accidentally. A lovely spot for lunch.

Top of Lantern, 1901, Mackintosh, pic courtesy Hunterian

Top of Lantern, 1901, Mackintosh, pic courtesy Hunterian

Cross through the University campus and make your way towards the far end of Argyle Street. Maggie’s Cancer Care Centre hosts a DNA spiral which you can see in passing from street level. It was created by co-founder of Maggie’s Cancer Care Centres Charles Jencks, also responsible for the one day a year wonder, the Garden of Cosmic Speculation.

Maggie’s Centre Glasgow, DNA seat with twisted

Maggie’s Centre Glasgow, DNA seat with twisted

waveform, Charles Jencks, 2002-2003

We’re off to the City Centre now. Hope on a bus or take a stroll to Charing Cross. Once there, look up, and say hello to Beethoven. On Renfrew Street (the other side of Sauchiehall Street) a Beethoven bust looks out from this B-listed building upon the locals. Above what used to be a former piano shop, T A Ewing’s Piano and Harmonium Emporium, it was sculpted by the owner’s brother, James Alexander Ewing.

Beethoven, James Alexander Ewing, circa 1897 pic Geograph.org

Beethoven, James Alexander Ewing, circa 1897 pic Geograph.org

Continue down and while familiar to University of Strathclyde students if you’re not a resident of the area you’re in for a treat. Rottenrow Gardens used to be the location of a former maternity hospital, The Rottenrow, opened 1834. Now demolished, the archways remain and in tribute a metal sculpture of a giant safety pin. So the story goes, pregnant women were walked up and down the steep hill to stimulate labour – and it worked!

Monument to Maternity/Mhtpothta, George Wylie, 2004

Monument to Maternity/Mhtpothta, George Wylie, 2004

There are many wonderful sculptures distributed across the city, what others are your favourites?

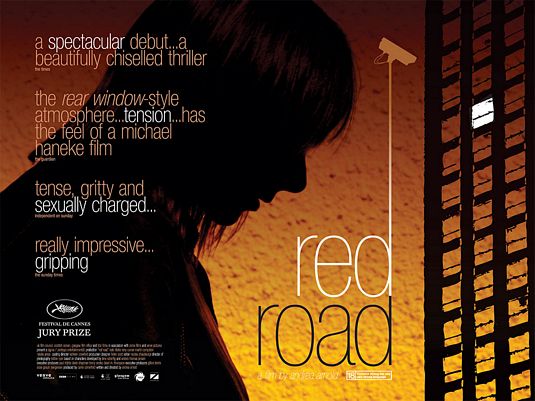

Red Road

Director Andrea Arnold Cast Kate Dickie, Tony Curran, Martin Compston UK/Denmark, 2006

Red Road (2006) marks a particular peak in Scottish film making. A culmination of cross-country exchange and creative development, it proved a critical success, going on to win the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes. It was the first of a planned trio of films as part of the Advance Party project, a collaboration between Glasgow-based Sigma Films and Zentropa of Denmark. With elements filtering through of the Dogme95 movement and its pre-requisites, Advance Party contained its own specific criteria. This set of stipulations revolved around limiting the budget, shooting duration and filming digitally. There was also a specific focus on guiding first time feature filmmakers, which led to the involvement of Red Road writer/director Andrea Arnold.

It was Arnold’s short film Wasp (2003) which lay as a precursor to Red Road. It captured a snap shot of a young mum’s life, her four children in tow wherever she was to go, struggling to feed and clothe them. Keeping the camera close and untethered toward her female family, a precarious unpredictable quality emerged which translated well to the storytelling in Red Road. Also brought over was the short’s lead actress Natalie Press, who stars here as Martin Compston’s girlfriend. The characters to appear across all the Advance Party films were developed between Lone Scherfig and Thomas Andersen of Zentropa, but they were brought to life under Arnold’s precise guidance.

The film follows Jackie (Kate Dickie) a CCTV operator based in Glasgow, intricately unpicking the journey which has led her there. Jackie oversees the movements of a corner of Glasgow life from her monitor desk. Faced by a bank of screens, Jackie reigns omnipotent as she zooms, controls, and pieces together the fragments of the inhabitants’ lives. A scope of control all the more vital, relevant, because it has been unavailable to her privately. The grid-like assortment of screens both visualises the co-existence of people who live alongside each other and yet never meet despite their close proximity, while revealing unexpected connections.

When Jackie unexpectedly spots Clyde (Tony Curran), a recently released prisoner with whom she has an as yet unexplained connection, she crosses the barrier from screen to street. Falling into real-life pursuit, Clyde becomes her target. The nature of his connection to her is withheld from the audience for most of the film’s duration, and the increasing tension is reflected in frequently unsettled, chaotic outbursts between characters. Whoever he may be to her, the camera, and the perspective, stay firmly with Jackie. The towering Red Road blocks, from which the film takes its name, are clouded in dank gloom, enhance the sensation of foreboding. Incrementally, the reasons behind Jackie’s removal from family life, her stoical expression, her self-enforced detachment, are revealed.

The lean production format is mirrored within the film’s content, for example dialogue is utilised sparsely, and the iconic, though now party demolished, Red Road flats are laid bare. There is a development of filmic style, where a European art house aesthetic can be perceived. This is a woman’s experience set amongst a recognisable, though fractured, Glasgow, but it is in the ambiguity, the shadows and the silhouettes, and the floating carrier bag seen thrashing through the air, which attest to an alternative sensibility. Jonathan Murray comments on this in The Cinema of Small Nations (2007) when he says, “The early 2000s witnessed a collective turn to Europe that was aesthetic, thematic and industrial in nature. …these films manifested a shared desire to explore private experience and complex, extreme psychological states, rather than exploit popular genres and conventional narrative forms. [1]” Red Road, then, followed further the filmmaking path as observed by the likes of fellow Scottish productions at the time such as Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (Scherfig, 2002), and Morvern Callar (Ramsay, 2002).

Beyond Red Road, Arnold has made further features including Fish Tank (2009) and Wuthering Heights (2011). Fish Tank in particular took themes explored in her previous work, featuring a young woman struggling with her circumstances and familial relationships. Leaving Glasgow for an Essex setting, there is a perceptible return to the waspish roots of her first foray. It is in Red Road however that an establishment in feature filmmaking was made, and with it a valuable, distinctive, contribution to Scottish film.

Originally commissioned for Glasgow Film Theatre.

[1] Hjort, M and Petrie, D (eds) (2007) The Cinema of Small Nations, Edinburgh University Press.

Get festive Scottish style with the Clootie Dumpling…

https://munchies.vice.com/en/articles/youll-need-four-hours-and-a-pillowcase-to-make-this-dumpling