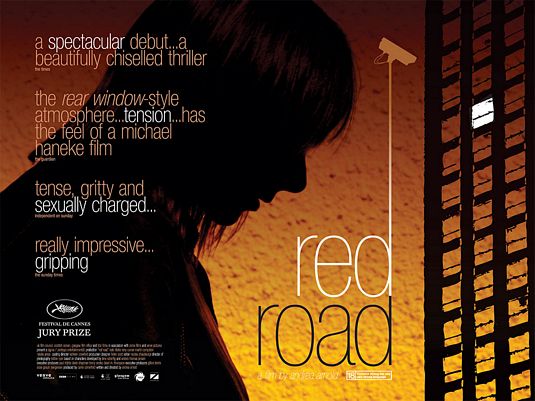

Red Road

Director Andrea Arnold Cast Kate Dickie, Tony Curran, Martin Compston UK/Denmark, 2006

Red Road (2006) marks a particular peak in Scottish film making. A culmination of cross-country exchange and creative development, it proved a critical success, going on to win the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes. It was the first of a planned trio of films as part of the Advance Party project, a collaboration between Glasgow-based Sigma Films and Zentropa of Denmark. With elements filtering through of the Dogme95 movement and its pre-requisites, Advance Party contained its own specific criteria. This set of stipulations revolved around limiting the budget, shooting duration and filming digitally. There was also a specific focus on guiding first time feature filmmakers, which led to the involvement of Red Road writer/director Andrea Arnold.

It was Arnold’s short film Wasp (2003) which lay as a precursor to Red Road. It captured a snap shot of a young mum’s life, her four children in tow wherever she was to go, struggling to feed and clothe them. Keeping the camera close and untethered toward her female family, a precarious unpredictable quality emerged which translated well to the storytelling in Red Road. Also brought over was the short’s lead actress Natalie Press, who stars here as Martin Compston’s girlfriend. The characters to appear across all the Advance Party films were developed between Lone Scherfig and Thomas Andersen of Zentropa, but they were brought to life under Arnold’s precise guidance.

The film follows Jackie (Kate Dickie) a CCTV operator based in Glasgow, intricately unpicking the journey which has led her there. Jackie oversees the movements of a corner of Glasgow life from her monitor desk. Faced by a bank of screens, Jackie reigns omnipotent as she zooms, controls, and pieces together the fragments of the inhabitants’ lives. A scope of control all the more vital, relevant, because it has been unavailable to her privately. The grid-like assortment of screens both visualises the co-existence of people who live alongside each other and yet never meet despite their close proximity, while revealing unexpected connections.

When Jackie unexpectedly spots Clyde (Tony Curran), a recently released prisoner with whom she has an as yet unexplained connection, she crosses the barrier from screen to street. Falling into real-life pursuit, Clyde becomes her target. The nature of his connection to her is withheld from the audience for most of the film’s duration, and the increasing tension is reflected in frequently unsettled, chaotic outbursts between characters. Whoever he may be to her, the camera, and the perspective, stay firmly with Jackie. The towering Red Road blocks, from which the film takes its name, are clouded in dank gloom, enhance the sensation of foreboding. Incrementally, the reasons behind Jackie’s removal from family life, her stoical expression, her self-enforced detachment, are revealed.

The lean production format is mirrored within the film’s content, for example dialogue is utilised sparsely, and the iconic, though now party demolished, Red Road flats are laid bare. There is a development of filmic style, where a European art house aesthetic can be perceived. This is a woman’s experience set amongst a recognisable, though fractured, Glasgow, but it is in the ambiguity, the shadows and the silhouettes, and the floating carrier bag seen thrashing through the air, which attest to an alternative sensibility. Jonathan Murray comments on this in The Cinema of Small Nations (2007) when he says, “The early 2000s witnessed a collective turn to Europe that was aesthetic, thematic and industrial in nature. …these films manifested a shared desire to explore private experience and complex, extreme psychological states, rather than exploit popular genres and conventional narrative forms. [1]” Red Road, then, followed further the filmmaking path as observed by the likes of fellow Scottish productions at the time such as Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (Scherfig, 2002), and Morvern Callar (Ramsay, 2002).

Beyond Red Road, Arnold has made further features including Fish Tank (2009) and Wuthering Heights (2011). Fish Tank in particular took themes explored in her previous work, featuring a young woman struggling with her circumstances and familial relationships. Leaving Glasgow for an Essex setting, there is a perceptible return to the waspish roots of her first foray. It is in Red Road however that an establishment in feature filmmaking was made, and with it a valuable, distinctive, contribution to Scottish film.

Originally commissioned for Glasgow Film Theatre.

[1] Hjort, M and Petrie, D (eds) (2007) The Cinema of Small Nations, Edinburgh University Press.